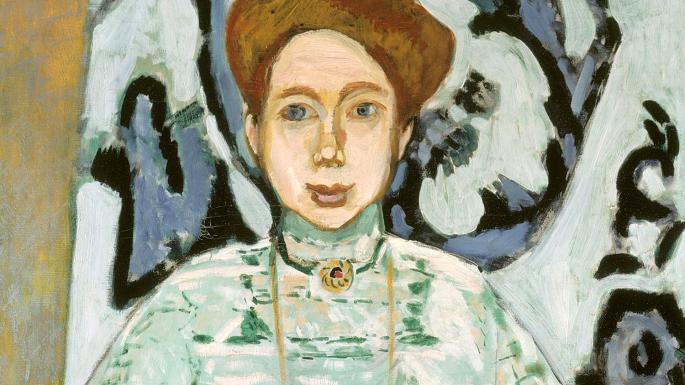

The National Gallery is defending its position over the 100-year-old Matisse masterpiece at the centre of a £24.6 million legal row, with claims that it was stolen. The portrait is of Greta Moll, Matisse’s muse, and her descendants are now claiming the painting was taken from the family after the Second World War during Nazi looting.

“Litigation is a continuation of business by other means.” This adaptation of the quote from Carl von Clausewitz in his seminal book, On War, is probably truer than ever. Indeed, nowadays litigation is often the chosen route to resolve corporate battles, to protect intellectual property, to settle family clashes, and the list goes on. Disputes in the art market were a notable exception to the global litigation frenzy — not so much because the art market saw fewer rows, but rather they were mostly dealt with out-of-court.

More recently, however, litigation in the field of art and cultural property has increased, mainly driven by the huge sums often at stake in today’s art market. Sometimes the claimant brings legal action only to put pressure on galleries, auction houses or museums, which prefer not to be in the public eye over matters that question their scrupulousness or due diligence. Another reason for this increase is the controversial development of “litigation funding”, whereby a third-party professional funder pays the claimant’s litigation costs in return for a share of the proceeds if they win.

The types of art disputes vary substantially: they may regard the sale or loan of artworks, art insurance or shipping contracts, exhibition contracts, contracts between artists and galleries, the artist’s resale right, the right to reproduce a copyrighted work of art, the restoration of cultural goods, and the return of cultural property to the original owner, to name but a few. More recently, the press has widely reported famous cases of alleged forgeries and attempts to recover artwork looted by the Nazis.

These types of litigation are often very complex due to the need to reconstruct old historical events, to obtain expert opinions from leading scholars, to resolve intricate conflicts of law, etc. And with this come high legal costs, lengthy proceedings, and many uncertainties.

The forerunner of this trend is the WIPO-ICOM Art and Cultural Heritage Mediation established in 2011 by the World Intellectual Property Organization and the International Council of Museums.

This year the Arbitration Chamber of Milan launched a new venture to promote alternative dispute resolution methods in the field of art and cultural property. The initiative has been warmly welcomed by all art market players as a useful alternative and efficient method of resolving conflicts amicably — avoiding lengthy and expensive proceedings in Italian courts. And within just a few months, the chamber has successfully mediated several cases in the field of modern and contemporary art. More significantly, the initiative has received strong endorsement from the national associations of both art galleries and antiques dealers.

The success of this endeavour could potentially serve as a model to adapt in other jurisdictions. Only time will tell whether this trend will consolidate and mediation will become a serious alternative to court . Usually, bad habits die hard. But in this case, there is cause for optimism because all the stakeholders share a common interest in avoiding the type of aggressive litigation that ultimately harms the very reliability of the art market.

Alberto Saravalle